What does this mean for me? Sometimes I feel as if I am a twin tree, two trunks reaching for the sun but connected to the same roots. Traveling to new places is in my blood, and although my grandmother thought assimilating in public was the best route for herself and her three boys, she never lost sight of who she was behind closed doors. On the other hand, my grandmother was a Japanese American woman who moved here shortly after World War II to wed my grandfather, a Baptist from rural North Carolina. I grew up in America in a racially segregated town, and so much of what I learned growing up was based on Eurocentric values and the myth of meritocracy. First, I may be white assumed, but I identify as multiracial my roots are a combination coming from different trees, making a web of sometimes contradictory beliefs and norms. There are many things my “leaves” communicate to people, some of which are correct and some not so. As far as the eye can see, I am a white woman, probably an educator, and most likely work for equity and social justice. I am currently wearing jeans with comfortable sneakers, and my shirt says “Don’t Erase History” with books, one I bought this past summer at the Human Rights Campaign store. On the surface level, my leaves are quite unassuming. But do we know ourselves? What would our trees look like? Just as it’s important to get to know our students, they need to get to know us. In my student experience, teachers would always ask me about my culture, but then never share about theirs. (We also dive deeper into Zaretta Hammond’s work in our Touchstone Texts for Equity course, which uses her Culturally Responsive Teaching & the Brain as a seminal text for creating more equitable classrooms.) Part of this learning process is to make the unseen seen, which is where Zaretta Hammond’s cultural tree comes in.

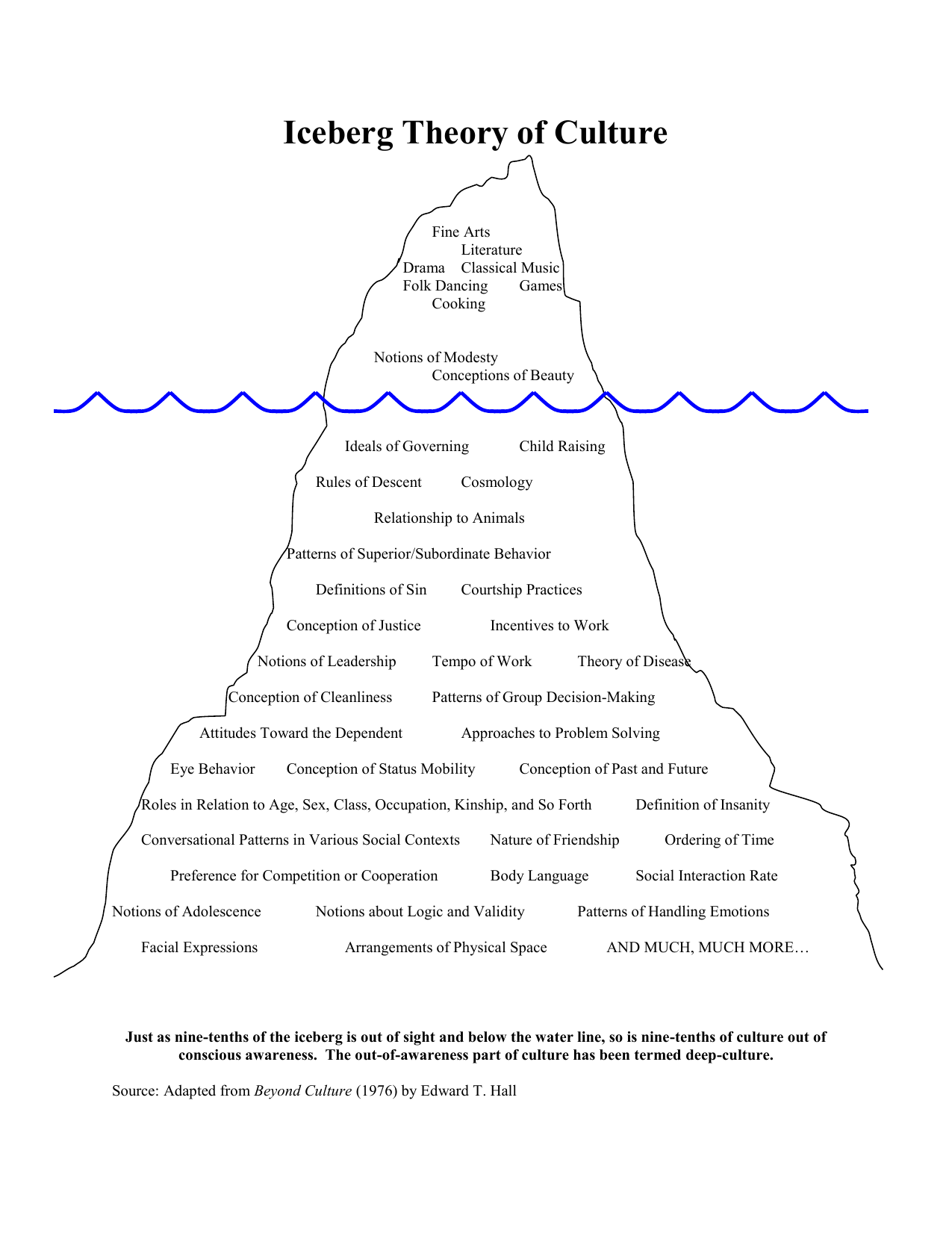

This encourages educators to recognize that what they see is only a small fraction of culture, and to be truly culturally responsive and sustaining, educators have to be aware that 90% of culture is invisible. Most educators are familiar with Hall’s “cultural iceberg” model, which uses the physical makeup of an iceberg as a metaphor for culture 10% of an iceberg is seen above water, while the other 90% is below the surface. In the NYC DOE’s Mission and Vision statement, they explain why CRSE is so important and how educators can ensure their units, lessons, and activities are culturally sustaining.īut how do we define culture, and do we know our own cultures well enough to help our students discuss theirs? CRSE, or Culturally Responsive and Sustaining Education, has become a focal point for many districts across the nation, including the New York Department of Education.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)